LICI Shares a Presentation at the August 13, 2025 Abbeville CRCL Meeting

- LICI

- Aug 13, 2025

- 13 min read

Updated: Sep 4, 2025

August 14, 2025 Abbeville, La.

The Louisiana Iris Conservation Initiative (LICI) participated in the Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana's (CRCL) Coastal Restoration Roadshow held in Abbeville, Louisiana, on Wednesday, August 13th. LICI’s president, Gary Salathe, attended the meeting, joined by a member of the family that owns the largest tract of land in the Turkey Island Swamp, now known as the Abbeville Swamp, with whom LICI has been working closely.

The purpose of the roadshow was to allow CRCL staff to hear directly from the public about the challenges facing their communities and their ideas for potential hurricane protection or habitat restoration projects. This outreach is an important step in broadening CRCL’s efforts into southwest Louisiana.

During the table discussions, Salathe shared photos and information from LICI slide presentations he has given to various civic groups and governmental bodies over the last two years. Here is his presentation:

LICI is studying the decline of irises in Turkey Island Swamp and restoring them in Palmetto Island State Park.

Its possible that some clumps of irises may also survive in other swamps, by seeds carried down the Vermilion River.

The Turkey Island Swamp, better known to Louisiana iris enthusiasts as the Abbeville Swamp, is the historic home of the I. nelsonii species of Louisiana iris, known as the Abbeville Red iris.

Maps from the 1930s and 1940s show colonies of I. nelsonii irises on lands south of the Abbeville Swamp. One of these sites was in the swamps of what is now Palmetto Island State Park. It is believed that these colonies were established by I. nelsonii seeds carried downstream along the Vermilion River from the Abbeville Swamp.

The Abbeville Red iris was well known to residents living near the Abbeville Swamp prior to the late 1930's. Because this area was also home to the red I. fulva species of Louisiana iris, many people—even to this day—have believed that the Abbeville Red iris was simply a larger and more exceptional form of I. fulva.

It wasn’t until local Abbeville

resident and amateur horticulturist W. B. MacMillan ventured deep into the Abbeville Swamp during the late 1930's and observed the red irises growing there that the idea began to take hold that this plant might, in fact, represent a new species of Louisiana iris.

Word quickly spread throughout iris world that an as-yet-unknown species of Louisiana iris might exist in the remote Abbeville Swamp. People flocked to the swamp to collect huge numbers of this rare and exotic new plant.

A few mail-order Louisiana iris nurseries began offering I. nelsonii for sale, further fueling demand. (Left: a 1952 catalog page from an Acadiana-based mail-order company that had already been selling Abbeville Red irises for years.)

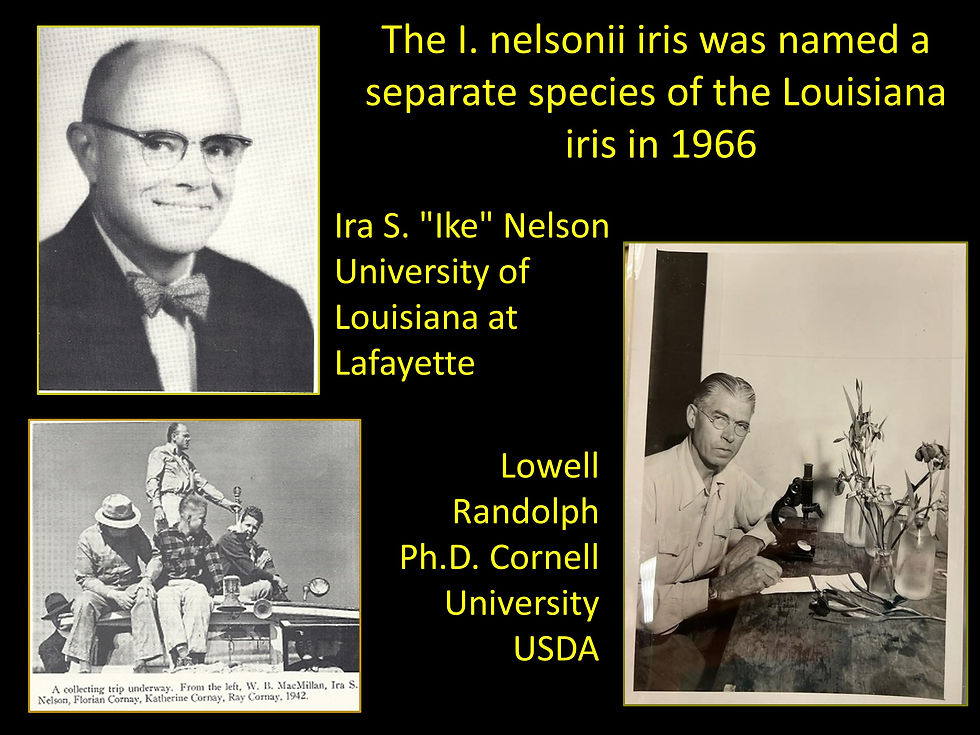

The mystery drew the attention of Ira Nelson, a horticulture professor at what is now the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. From the 1940s until his untimely death in 1965—just a year before the Abbeville Red iris would be officially recognized as a new species, Nelson was a leader in the early Louisiana Iris Society.

Nelson collaborated with Lowell Fitz Randolph, a Cornell University plant geneticist and internationally known iris expert, beginning in the mid 1940's. Together, they spent the following years studying the Abbeville Red iris and ultimately determined that it represented a distinct Louisiana iris species.

In 1966, Randolph formally described Iris nelsonii in Baileya, a scientific journal of horticultural taxonomy published by the Liberty Hyde Bailey Hortorium at Cornell. He named the species in honor of his friend and collaborator, Ira Nelson, who had died in a car accident the year before. It then became the fifth recognized Louisiana iris species.

In 1966, Iris nelsonii was officially recognized as the fifth species of Louisiana iris, joining the four previously known species.

Four of the five recognized Louisiana iris species occur naturally in Louisiana, and all four have been documented growing in the wild within Vermilion Parish.

The native habitat of the newly identified Iris nelsonii, a unique species of Louisiana iris, exists only in lower Vermilion Parish. It is the only place in the world where this iris grows naturally. The Abbeville Swamp, where it was first discovered, is believed to be the place of its origin.

The Abbeville Swamp (Turkey Island Swamp) is privately owned by numerous individual landowners, with access restricted by locked gates on surrounding roads. Over the years, many of the properties within the swamp have been divided through inheritance as family members passed away.

The largest single ownership within the swamp—representing a minority portion of the total area—is held by a family partnership.

More than a century ago, the family’s founding member requested that this tract never be divided, a directive that has guided ownership ever since. LICI has been working with this family, along with one other, to assess the current condition of I. nelsonii on their properties.

Prior to 1940, the only way water entered or exited the swamp was through Young’s Coulee, a small bayou whose upstream origin serves as a key drainage source for the Town of Abbeville.

The photo on the right was taken at the direction of a person who grew up along the edge of the Abbeville Swamp in the 1950s. His family's property backed up to Young’s Coulee, where he and his brothers and cousins spent many days playing, fishing, and hunting before the Coulee was dredged in 1969.

In 2024, they showed the photographer this offshoot of the Coulee to illustrate what Young’s Coulee looked like throughout its history. It was a narrow, shallow bayou, often blocked by fallen trees and dotted with grassy islands. In other words, it was not an efficient drainage-way, and tidal flow from the Vermilion River into the swamp was significantly reduced compared to today.

After repeated rain events caused severe flooding in Abbeville during the late 1930s, Young’s Canal was proposed, approved, and constructed in 1940 (shown in blue). Its route cut directly through the center of the Abbeville Swamp to the Vermilion River, creating a straight path for stormwater from the north and bypassing the smaller, debris-filled Young’s Coulee.

As was the custom with canal construction in south Louisiana at the time, the mud removed from the swamp to dig Young’s Canal was placed along its banks. This created what is known as a spoil bank—essentially a 4 to 5 foot-high levee.

Top left photo: Example of a barge-mounted crane used to dredge canals during the era when Young’s Canal was constructed.

To connect the swamp to the newly dug Young’s Canal, random openings were left in the spoil bank. In some cases, these gaps also allowed rainwater to drain from the higher, cultivated land.

Another major change to the hydrology of the Abbeville Swamp occurred in 1944 with the digging of the Four Mile Cut. Before this, the Vermilion River slowly meandered through the marshes before emptying into a shallow bay on the north side of Vermilion Bay, from which boats could access the Gulf of America. This final stretch of the river and its bay were prone to silting.

Following the construction of the Intracoastal Canal, the Four Mile Cut—an 80-foot-wide, 8-foot-deep channel through the wetlands—was created to bypass the winding lower Vermilion River. The project improved water flow through the Vermilion River, and therefore the Abbeville Swamp, and facilitated navigation for new boatbuilding businesses in southern Vermilion Parish that emerged after the United States entered World War II.

The Four Mile Cut canal increased the Vermilion River’s capacity to carry storm-water runoff from major upstream rain events by providing a direct route to Vermilion Bay and the Gulf of America.

With the Louisiana offshore oil drilling boom, more businesses were established on the lower Vermilion River to support Gulf of America drilling rigs. Centered around the new town of Intracoastal City, the area transformed from a fishing village into an industrial hub. The Four Mile Cut made this development possible by providing navigable access to the Gulf.

However, an unintended consequence developed over the years: as the Four Mile Cut widened due to erosion from increased boat traffic wakes, tidal flow from the Gulf of America extended further upstream. This also worsened an existing problem of saltwater intrusion during the dry fall months, when upstream freshwater flow in the Vermilion River was reduced.

A more serious unintended consequence became evident during tropical weather events. The canal created a direct path for storm surge from the Gulf of America to travel up the Vermilion River. This effect mirrors what occurred with the Mississippi River–Gulf Outlet Canal (MRGO) in Southeast Louisiana, completed in 1968 to boost New Orleans’ shipping industry. Following its completion, cypress swamps along the MRGO began to die off as Gulf saltwater moved up the canal, and the problem worsened as the canal widened over time from erosion.

After extensive study and debate, the MRGO was closed in 2009, having been determined to contribute significantly to levee failures in St. Bernard and Orleans parishes during Hurricane Katrina. Fortunately, unlike the Four Mile Cut, the projected increase in economic activity from the MRGO never materialized.

In 1969, after continued flooding upstream of the Abbeville Swamp, another drainage improvement project was proposed, approved, and constructed by the Police Jury: the clearing of debris, widening, and deepening of Young’s Coulee (shown by the solid blue line; the dashed line marks Young’s Canal).

This project impacted the Abbeville Swamp similarly to the earlier construction of Young’s Canal. By improving drainage through increased flow in Young’s Coulee, higher elevations of the swamp were left drier, and tidal flow originating from the Vermilion River was greatly increased.

As with the construction of Young’s Canal and the Four Mile Cut, this new drainage project helped to solve localized flooding problems, but it did so at the expense of further degrading the Abbeville Swamp.

As was done during the construction of Young’s Canal, random openings were left in the spoil bank to connect the swamp to the newly refurbished Young’s Coulee. One of these openings was connected to a wide ditch that had previously been used to pump irrigation water into the cultivated land, but is now used to allow rainwater to drain from this higher ground.

At the time the Abbeville iris was discovered in the late 1930s, water entered and exited the Abbeville Swamp in two primary ways.

First, through rain falling within the swamp itself, runoff from the surrounding higher land, and rising water levels in Young’s Coulee from rainfall in the upstream watershed originating at Abbeville.

Second, through the daily incoming and outgoing tides from the Vermilion River.

Because the last stretch of the Vermilion River before entering Vermilion Bay twisted and turned through the marshes on the north side of the bay, the influence of the daily tides was likely much reduced upstream from Intracoastal City. Young’s Coulee, a shallow, debris-filled bayou with fallen trees and small islands of cut grass, would have further diminished tidal impact within the Abbeville swamp.

Similar to areas on the west side of the Vermilion River near Palmetto Island State Park today, the incoming tide likely had little time to penetrate the swamp before the outgoing tide pulled it back out. In the upper reaches of the swamps near the park, the daily effect of tides is minimal—just as it likely was in the Abbeville Swamp prior to 1940. In these areas, water levels in the upper reaches are primarily maintained by rainwater.

The world changed drastically for the Abbeville Swamp and its irises after Young’s Canal and the Four Mile Cut were built, and Young’s Coulee was dredged and cleared of debris. The immediate impact was the drainage of some higher-elevation areas of the swamp. A less well-known but equally important effect was the increase in daily tidal flow in and out of the swamp. Areas that likely experienced very little daily water level change before the drainage improvements now regularly experience tidal ranges of 12 to 18 inches on normal days, and as much as 24 to 36 inches above normal high tide during sustained south or southeast winds pushing water from Vermilion Bay up the Vermilion River.

The chart in the upper graphic shows the predicted normal tide for one week in May 2024, with high tide ranging from 12 to 18 inches. This means any irises growing in the Abbeville Swamp that were not on higher ground—or at least 18 inches tall if on lower land—would be submerged for hours during high tide on most days that week.

However, twice during the month, strong south winds pushed water from the Gulf of America up the Vermilion River, causing the monthly tidal range (the difference between low and high tide) to increase to 4 feet during these multi-day events, with high tide likely reaching 30 to 36 inches, or up to 24" higher than normal high tide, as shown in the lower tidal chart. During any tropical weather event, even if distant, tides could be even higher for an extended period.

Since these conditions have persisted in portions of the Abbeville Swamp along Young’s Canal from 1940 and in Young’s Coulee since 1969, it is understandable that observers from the 1950s and early 1960s now report that irises once abundant in vast areas of the interior swamp have disappeared.

Written descriptions of the Abbeville Swamp from the mid-1940s already noted that irises were disappearing “due to the recent building of Young’s Canal,” and that some higher-elevation areas of the swamp had gone dry, with some of these areas starting to be converted into farmland.

By the mid 1960’s it was becoming apparent to iris aficionados from around the region that this new, fifth species of Louisiana iris could totally disappear from its native habitat in the coming years.

Unfortunately, this began a sustained period of iris collecting from the swamp by enthusiasts aiming to “save” or “preserve” them—a practice that, on a much smaller scale, continued into recent years. This further reduced their numbers in the swamp.

Left photo: Taken at low tide about 50 feet inside the swamp near an opening through the Young’s Coulee spoil bank. This was the only clump of Abbeville Red irises found in the entire area. The red lines on the trees mark the high tide level from the afternoon before.

The photo is from a 2024 LICI trip to the Abbeville Swamp to check for irises near the spoil bank openings. It was meant to answer the question of how many irises have survived in this zone. The answer was: very few.

Right photo: A healthy clump of irises growing on the spoil bank of an interior drainage ditch in the Abbeville Swamp in 2024. The muddy grass leaves at the base mark the high tide line, which left only about six inches of water around the plants. At this location, the irises could likely withstand even the very high tides pushed into the swamp from Vermilion Bay by strong south winds.

After several trips over the past two years, most of the irises in the swamp have been found either in a narrow band along the swamp’s higher elevations, on spoil banks of interior drainage ditches, or along the shoulder of interior farm roads—areas that allow the irises to stay above water during high tides and avoid prolonged flooding.

In 2022—and even more so in 2023—a prolonged drought in the Vermilion River watershed worsened the nearly annual problem of saltwater from the Gulf of America moving upstream. Despite the Teche-Vermilion Fresh Water District running their five massive pumps around the clock to divert water from the Atchafalaya River into Bayou Teche and the Vermilion River, the additional flow was not enough to stop this saltwater encroachment.

This posed yet another threat to the Abbeville Red irises in the Abbeville Swamp: saltwater intrusion. The photo above shows how close saltwater in the Vermilion River came to the openings into the swamp from Young’s Coulee during the fall of 2023, at the height of the drought. It was taken about 500’ from the first spoil bank opening into the swamp. At this point, salinity levels were high enough to kill the freshwater cut-grass growing along the coulee’s edge.

This shifted the issue of tidal flow into the Abbeville Swamp from being not just about preserving the irises to the realization that all plant life in the swamp—including its trees—may be faced with the destructive force of saltwater intrusion.

Since the beginning of LICI’s work investigating the condition of the Abbeville Red irises and the Abbeville Swamp, a relationship has developed with another landowner whose property lies along Young’s Coulee. Their land has been in the family for decades—well before the clearing and dredging of Young’s Coulee in 1969.

They personally witnessed the immediate impact of that dredging on their portion of the swamp: greater fluctuations in tidal flow and sustained, abnormally high tides whenever strong south winds pushed water upriver.

Left photo: A spoil bank was deposited when drainage ditches were dug decades ago along each side of their property to carry runoff from neighboring sugarcane fields. At the time this photo was taken during a high tide, there was about an 8-inch difference in water level between the ditch—fully open to Young’s Coulee—and the swamp on the 30-acre tract on the right. Right photo: The gated culvert installed by the 30-acre landowner to reduce tidal impacts from Young’s Coulee on their swamp. Before this structure was added, a 25-foot opening had been left in the Young’s Coulee spoil bank when the coulee was dredged in 1969.

Years ago, recognizing that the negative impacts were worsening each year, the owners of a 30-acre tract decided to act. With the support of the drainage board, they paid to have a gated culvert fabricated and installed at the single opening left to them after Young's Coulee was dredged.

Together with spoil banks that were created decades earlier by their neighbor on the two sides of their property—from drainage ditches dug to handle rainwater runoff from their sugarcane fields—the new gated culvert gave them the ability to effectively manage water levels within their swamp. Fluctuations were reduced to rainfall, seepage beneath the spoil banks, and a partial opening of the gate on the culvert to allow some tidal flow into the swamp. During infrequent extreme heavy rains, they could simply fully open their small “water control structure” to speed up the release of excess water.

This also greatly eased their concern about the annual fall saltwater intrusion moving up the Vermilion River, which seemed to worsen over time—likely due to the continued widening of the Four Mile Cut from erosion.

LICI’s surveys of the Abbeville Swamp over the last two years confirmed that more irises were growing in the lower areas of the swamp on the 30 acre property where the water level has been managed than in the same elevation areas of the swamp owned by their neighbor, where tidal flow could not be controlled.

Photos: All of the small-scale water control structures shown in the photos have been used for decades on the west side of the lower Vermilion River by landowners to manage water levels and protect their agricultural land from saltwater intrusion.

The upper-left photo shows a water control structure in Palmetto Island State Park that slows and limits the tidal flow coming into the park’s swamp and waterways from the nearby Vermilion River.

LICI believes that large areas of the Abbeville Swamp could once again support significant numbers of Abbeville Red irises if tidal impacts were returned to the conditions that existed before the drainage improvement projects—specifically the construction of Young’s Canal, the Four Mile Cut, and the dredging of Young’s Coulee—undertaken between 1940 and 1969.

Because the Abbeville Swamp now has many individual landowners, funding and organizing the installation of water control structures on a large scale would be a major challenge. For this reason, LICI has decided to focus its efforts on one landowner with whom they already have a strong partnership. The goal is to help them find funding to design, permit and install structures in five openings to protect several hundred acres of their swamp from the large daily fluctuations in tidal flow and to keep saltwater out during droughts.

Comments